Organs Without a Body: Painting the Boundaries and Extensions of Bodily Perception

【1. Introduction: Redefining the Body】

In my recent practice, the body is no longer regarded as a stable, organic whole, but as a perceptual field that is continually deforming, dissolving, and reassembling. Through painting, I depict the “interior world” of the body—ambiguous, undefined forms beneath the skin: organs, scars, apertures, and tissues. These images originate from physiological structures, yet they are not faithful anatomical renderings; rather, they are reconstructions of bodily experience, psychological feeling, and the affective residues of the unconscious. For me, painting is not merely an external representation of the body, but a rebuilding of its perceptual dimension.

In my understanding, the body is no longer a closed, organic system. The skin cannot completely separate interior from exterior; the boundary between inside and outside is constantly being permeated, disrupted, and exchanged. The body’s edge thus becomes a “blurred interface,” one that receives impacts and touches from the outside while continuously releasing inner breath, memory, and emotion. In painting, the relation between body and world appears as an ongoing resonance and interpenetration.

Earlier, the monster was a central image in my work. In my visual experience, the monster signifies both fear and alterity, and also the repressed self of the unconscious. At that time, I focused on the estrangement of appearance: deformed bodies, indistinct organs, ruptured skin. As the work progressed, however, I realized that what truly interests me is not the monster’s outward contour, but the “interior landscape of the body” it implies. This “interior” is not physical, but psychic and perceptual—a space formed by the interweaving of bodily experience, emotion, and the unconscious.

I have therefore clarified my working logic: in my painting, the external figuration of the body is the form, while the embodied perceptual experience is the core. Bodily images are broken down and reassembled on the picture plane, becoming a field of flowing energies. My practice seeks a “painterly philosophy of the body” that does not pursue representation so much as experience—how the body is perceived, touched, and brought into consciousness.

Within this exploration, I propose the notion of “Organs Without a Body,” as a reverse reflection on Deleuze & Guattari’s concept of the “Body without Organs.” For Deleuze, the Body without Organs is a generative body that resists functionalization and organization, a stance against social control and symbolic regulation. What concerns me, however, is another condition: when the body’s integrity collapses, the skin is peeled away, and the torso is dismantled, do the remaining parts—organs, skin, tissues—still possess perceptual and existential capacities? In other words, my “Organs Without a Body” is not about the loss of the body, but about how perception can continue, drift, and regenerate within the body’s remnants.

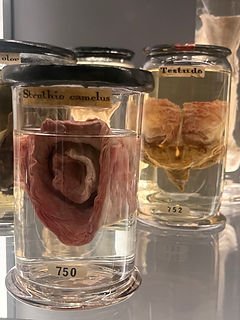

While studying in London, I visited the Hunterian Museum many times. It was a profoundly shocking visual experience. In transparent formalin jars, cut skin, exposed viscera, and congealed tissues float—at once biological and surreal. For the first time I realized that the body is not a unitary whole, but a network composed of countless interdependent yet independently existing fragments. This “fragmented real” brought a deep sense of estrangement. Gazing at those organs, I seemed also to be gazing at what is hidden in myself: the invisible, repressed interior.

At that moment I understood Julia Kristeva’s concept of abjection in Powers of Horror. Abjection names the collapse of borders—when the interior is exposed to the exterior, when the self faces what has been expelled, and the line between “I” and “not-I” gives way. Confronted with those preserved organs, I felt not only fear but a profound “self-estrangement”: in viewing another’s body, I was also facing the unconscious part of my own. Those preserved organs were like mirrors, reflecting my insecurity and vulnerability about existence.

This act of looking became the starting point for my painting. Here, painting is no longer a means of representation but a practice of perception—entering what language cannot reach through embodied actions (brush marks, scraping, accretion). As pigment piles, seeps, and flows across the canvas, I feel as if I am touching the limits of my own body.

【2. Skin, Scars and Apertures: The Body as Interface】

In my recent work, skin has become a crucial visual and conceptual motif. It is both protection and boundary; the site of self-identification and the entry point of the other. As psychoanalyst Didier Anzieu writes in The Skin-Ego (1989), skin is not only a physiological structure but also a psychic defense. It is the first line between the individual and the outside world, defining how we perceive “self” and “other.” When this line is torn, perforated, or damaged, we are forced to confront the mingling and confusion of inside and outside.

In my paintings I repeatedly depict fissures, apertures, and torn tissues. They are visual evidence of the skin’s collapse and also channels for perception. I often keep these areas deliberately ambiguous and indeterminate, preventing viewers from securely naming what they see—is it a wound, a breathing pore, or an unhealed scar? This ambiguity releases the body from being a closed figure and allows it to function as an energetic interface.

Technically, I use varied brushwork and layered color to construct a “tactility” of skin. Wet strokes simulate seeping fluid; heavy impasto gives the surface a palpable thickness. I often use flesh-pinks, grey-whites, and dark reds—colors carrying the warmth of flesh yet tinged with coolness. This interweaving of warm and cool makes the skin feel both intimate and unsettling.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s painting has been an important catalyst. Through extreme close-up and gentle gradation, she renders petals, caverns, or clouds as folds and openings akin to the female body. Her light and composition—almost liturgical—elevate these private forms into the sacred. Her work suggests the body’s surface can be re-seen: skin is not only a covering of flesh, but a spiritual landscape.

A particularly striking example is O’Keeffe’s Purple Hills. The painting presents an undulating red-brown landscape that simultaneously evokes the sensuousness of skin and the stillness of geological form. O’Keeffe once wrote, “I feel so at home here—so quiet—when I walk among the red hills, my skin feels close to the earth.” This statement reveals how she perceived the landscape through bodily intimacy: the earth is not an external scene but an extension of the skin itself. In Purple Hills, the smooth, velvety texture of the slopes and the soft gradations between shadow and light transform the mountain into a metaphor for flesh—an immense, breathing body merging with the horizon. The boundary between land and body dissolves; the surface of the earth becomes a kind of epidermis that both shelters and exposes.

This understanding of landscape as skin resonates deeply with my own practice. Like O’Keeffe, I regard the surface of the body not as a limit but as a site of contact—a terrain where inner sensation meets external space. Her Purple Hills thus offers a visual metaphor for permeability: the skin of the earth and the skin of the body mirror one another, both vulnerable and receptive.

This “spiritualized skin” reshaped my approach. When I treat skin in painting as a carrier of emotion and memory, I realize that skin is a medium of perception. Once exposed to sight and touch, it reveals not only internal tissue but deep psychic structure. It archives affect and memory—personal experience inscribed on the body’s surface.

Thus, the skin in my pictures is unstable: it seeps, splits, and curls as if breathing. Openings signify not merely wounds but flows of energy. When skin ceases to be a barrier and becomes a channel for exchange, the body’s boundary is redefined.

This rethinking of skin has led me to ask continually in painting: can the outer layer of the body become an arena of emotion? Can painting render visible the invisible psychic experience? My answer is yes. The flow of pigment and the speed and thickness of brushwork give shape to a permeable body.

【3. Organs Without a Body: Persistence and Fragmented Perception】

Deleuze and Guattari’s “Body without Organs,” developed in Anti-Oedipus (1977) and A Thousand Plateaus (1987), is a key concept naming a body that resists organization and social coding. In their account, society, language, and the distribution of desire functionalize the body, taming it into a system: eyes for seeing, mouth for speaking, heart for beating. The Body without Organs undoes this regime, becoming a de-centered, de-organized flow of intensities.

This concept inspired me, but it also provoked a reverse question. Deleuze seeks to free the body from the tyranny of its organs; I ask: when the body collapses, can its organs still “perceive”? When bodily order disappears, do the remaining fragments still carry life?

Hence my concept of “Organs Without a Body.” In my understanding, organs that have lost the body’s structural frame remain nodes of perception. They are like drifting shards of consciousness, bearing sensory memory and affective energy, continuing to “breathe” in painting through ambiguous forms.

On the canvas these “organs” rarely appear as specific anatomical features; they are abstracted into color masses, vortices, and rhythmic overlaps. They extend perception rather than symbolize function. No longer belonging to a single body, they become residual perceptions floating in pictorial space.

This thinking recalls Jean-Luc Nancy’s claim in Corpus (2008): “The body is not a whole that possesses organs, but the coexistence and resonance among organs.” Meaning arises not from centralized unity but from relations among fragments. My painting unfolds within such fragmentary resonance.

I also see the life of fragments in Francis Bacon’s work. His figures are twisted and torn; organs break free of functional constraints and emerge as sites of emotion and pain. As Deleuze writes in The Logic of Sensation (2003), “The body is no longer an organism, nor a sum of organs; it is a field of intensity, a Body without Organs—a domain of flows and thresholds.” In my work, I attempt to make this “field of intensity” operate in reverse: to let disassembled organs continue to generate in their incompleteness.

Similar ideas appear in the work of Louise Bourgeois and Jenny Saville. Bourgeois’s soft sculptures, constructed of fabric, assemble fragments of the body that are fragile yet taut. Saville’s thick, translucent layers make enlarged, transformed flesh carry new emotional gravity. Both explore how parts of the body can perceive themselves. Their practices resonate with my notion of “Organs Without a Body.”

In my painting, those floating, unnamed forms are precisely such continuing organs. They are not anatomical things but psychological remains. They breathe, tremble, extend—still “alive” in another way after the body is gone.

【4. Painterly Language and Method: Thickness, Stroke and Layered Space】

In earlier stages, working with watercolor and acrylic, I was more concerned with planar composition, chromatic relations, and formal rhythm. As I deepened my engagement with oil painting, I gradually realized that a picture’s force lies not only in its imagery but in its material presence. The thickness, sheen, and flow of paint carry bodily energy in themselves.

In recent works, I devote greater attention to layering and thickness. I have drawn on the practices of Mamma Andersson and Chaïm Soutine—their repeated accretion, scraping, and overpainting generate depth and a breathing surface. This physicality of brushwork taught me that painting is not only a language of images but an extension of bodily action.

I began to strengthen the tactile dimension of my process. Paint moves on canvas like the rise and fall of skin, like breath—sometimes compressed and forced out, sometimes diluted and flowing. Through repeated actions—smearing, scraping, covering—the picture sways between life and erasure.

This past summer, at Pace Gallery in Hong Kong, I saw Lee Hyegjeong’s exhibition Tongue of Fire. The oily, liquid surfaces—hovering between fluid and set—felt like blood flowing or muscle breathing. Back in the studio I increased the proportion of medium to make pigments more transparent and supple. The pictorial space grew richer; the flow of paint and the breathing of brushwork produced a rhythmic resonance.

In this state, painting becomes a bodily act. Each mark is not a visual mimicry but a conversation between body and matter. The painting’s “breath” comes from contingency—from uncontrolled runs, accidental mixtures, and the sediment of pigment. Such contingency gives the work its life.

The pairing of thickness and gloss also led me to think about the relation between skin and organs. The texture of pigment feels like an extension of skin—soft yet vulnerable, both wrapping and permeating. These textures continually push the space of the image, compelling the gaze to pierce the surface and enter deeper layers.

【5.Painting in Practice: Formation and Ambiguity】

My latest painting (see Fig. 1) continues to explore the interior landscape of the body. There are no explicit bodily structures or identifiable organs; instead, the picture is built from ambiguous, flowing forms. They sway between heaviness and lightness, as if poised at the threshold between formation and dissolution. Large curved masses evoke swelling muscle, undulating viscera, or roiling cloud—moving between the material and the immaterial.

This ambiguity is precisely the visual state I pursue: freeing the body from the constraints of mimesis and transforming it into an open field of perception. The piling and diffusion of pigment produce a rhythm akin to breathing. Temperature in color—flesh-pinks, deep reds, and blue-greys—creates an atmosphere both intimate and uneasy. These colors blur boundaries between interior and exterior, body and space, pulling viewers into an ongoing, unnamable condition.

The work also crystallizes the core of “Organs Without a Body.” The forms seem detached from any bodily whole, yet they continue to breathe and pulse. They no longer bear function, but the rhythm of life persists. This recalls Deleuze’s “field of intensity”: a body that persists as energy after de-structuring. In my work, it is instead the organs that, once separated from the body, continue to grow visually and emotionally.

The painting’s softened edges extend my reflection on skin. Outer forms are not ringed by firm contours; they stretch softly and permeably, merging with the background. This blurred boundary symbolizes the interpenetration between body and environment, echoing my understanding of the body as interface. Skin is no longer isolation but a conduit for breath and energy.

Thus painting becomes a bodily practice—through gesture, tempo, and rhythm, I construct a space that can be perceived. Painting ceases to “depict” the body; it generates it. The body exists on the canvas in another form—fragmented, indistinct, yet still vivid.

【6.Conclusion: Painting as Exploration and Generation】

Looking back at this phase, I increasingly recognize that painting, for me, is not an endpoint of expression but a continuous process of research and generation. Painting is not only a visual language but a way of thinking.

The images of skin, scars, and organs were not predetermined symbols; they arose naturally during making—as responses to my thinking about body, perception, and existence. Each brushstroke, accretion, or scraping is an exchange between body and material. The flow, sedimentation, and setting of pigment concretize my reflections on bodily boundaries and emotional fluctuations.

Ultimately, “Organs Without a Body” has become a metaphor for my relation to painting. It reminds me that perception is never dependent on wholeness; it is continually produced in fragmentation, flow, and uncertainty. Painting therefore is not only a medium for representing the body, but a process that extends perception and generates meaning.

As painting-as-research, it allows thought to be generated through embodied action rather than merely explained. As Jean-Luc Nancy suggests, “The meaning of the body does not lie where it is named, but in the way it coexists.” Painting is precisely such a process of coexistence—linking body, matter, and thought, allowing perception to unfold in its unfinishedness.

In the end, I hope to let ambiguity persist in painting, to allow the undefined to keep breathing. Painting becomes the skin between me and the world—sensitive and resistant, permeable and regenerative.

Bibliography

Anzieu, D. (1989) The Skin-Ego. Translated by C. Turner. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Deleuze, G. (2003) Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. Translated by D.W. Smith. London: Continuum.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1977) Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by R. Hurley, M. Seem and H.R. Lane. New York: Viking.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by B. Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kristeva, J. (1982) Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by L.S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press.

Nancy, J.-L. (2008) Corpus. Translated by R.A. Rand. New York: Fordham University Press.

Specimens at the Hunterian Museum , London, photographed in 2025.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Purple Hills 1935, oil on canvas, 40.6 x 76.2 cm,Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS

Francis Bacon, Study for Three Heads, 1962, oil on canvas, MoMA

Lee Hyegjeong, parts of paintings, oil on canvas

Poetic organ, oil on canvas, 2025, Fig. 1